Every time the Americans threaten Canada (itself not an infrequent event), the War of 1812 immediately falls off the tongues of Canadians from coast to coast to coast. There’s nothing more that Canadians enjoy than a yarn about “that time we burned down the White House,” but reality doesn’t hold up to myth.

Canadians have a poor grasp on our own history and a shockingly ignorant grasp on military affairs today. I’ve written before about the way we remember history in my article ‘Good Guy Militarism,’ in which I observe that the way Canadians remember our military exploits gives us an over-inflated sense of militarism that the events themselves cannot live up to under scrutiny. In no example is this more apparent than the War of 1812.

Having written about the threat Canada faces from the USA, I have heard more “we’ll beat them like in 1812,” than one should hear in one lifetime. I have been emphatic that in the face of this crisis to Canada’s sovereignty and existence, there is no military solution, and I very much mean it. To explain why there won’t be “another 1812,” it’s time we take a quick look at 1812.

Canada, Britain and the United States in 1812

In 1812 “Canada” was not a unified nation, or even colony. Upper Canada comprised what is now Ontario, Lower Canada; Quebec. The Maritime provinces were again, separated entities. The term “Canadians” referred to francophone Canadians from Quebec only. The rest of the settler population identified as British.

The Canadas, especially Upper Canada of 1812, were frontier regions. Communications were very poor with the majority of trade and transportation travelling via the Great Lakes. Beyond Lake Erie, lay the territory claimed by the Hudson’s Bay Company, which at this time was mostly still occupied by Indigenous nations. Canada was a slave owning colony, featuring plantations of mixed Indigenous and African slaves.

Canada was a far from secure place for the British Empire. The population of Lower Canada was largely Francophone and Catholic and were French citizens one generation before. In Upper Canada was majority of the population were Americans. Some were Crown loyalists who had fled in the wake of the Revolution, but the majority had moved to Canada since US independence, attracted by land grants on the frontier. Thus when the war broke out, far from relying on a population of loyalists, the British were extremely worried about large-scale collaboration or revolt in favour of the Americans.

The United States was a new country in 1812 and had only just begun to expand beyond the original Thirteen Colonies. Much of the borderlands between Canada and the United States was wilderness, lakes or fast running rivers. The Northwest Territory, the region that now comprises Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, was heavily contested by the Indigenous Peoples who were suffering from increased violence and expansion since American Independence.

The United States Navy was very small, having only recently been founded, and the United States Army was likewise small, relying heavily on part time militias to make up for its size. These were locally raised and led by individual states, and with varying degrees of motivation and effectiveness. The US militia system had proved effective in the Revolutionary War and the wars of expansion targeting Indigenous Nations. It was voluntary, and the militiamen were not obligated to leave the borders of the US, which would have dire consequences.

The benefactor and colonizer of Canada, Great Britain, was in 1812, one of the most power empires in the world, but it was embroiled in conflict. Britain had experienced only one year of peace since 1792, and since 1807, had been fighting Napoleon. At sea, the Royal Navy maintained far and away the largest fleet in the world and used it to blockade much of the trade going to the European contentment. To Britain, the Canadas were backwaters; settler societies whose main produce was acting as a thoroughfare for the fur trade. In 1812, the British Army had less than 10,000 troops on the North American continent.

The Royal Navy was suffering a manpower crunch. This wasn’t, as is popularly believed, a lack of personnel, but rather a lack of trained sailors. Service on a warship was tough, disease was rife, and the dangers even in peacetime were constant. The US had the second largest civilian fleet in the world, it paid well, and many British sailors left to serve in it. Blockade duties and an ever-growing navy had thus left the Royal Navy in a state of crisis, and they turned to impressment. A form of navy conscription, impressment came to be symbolized and reviled because of the Chesapeake Affair (1807).

The USS Chesapeake, a US Navy frigate, was attacked by the Royal Navy’s HMS Leopard. The incident occurred after the Chesapeake’s captain refused to allow the British ship to board his in search of deserted Royal Navy men that they could re-impress. In the end, four US Navy men were killed, 17 were wounded, and four Royal Navy deserters seized. It was a humiliation for the Americans, and calls for war started immediately.

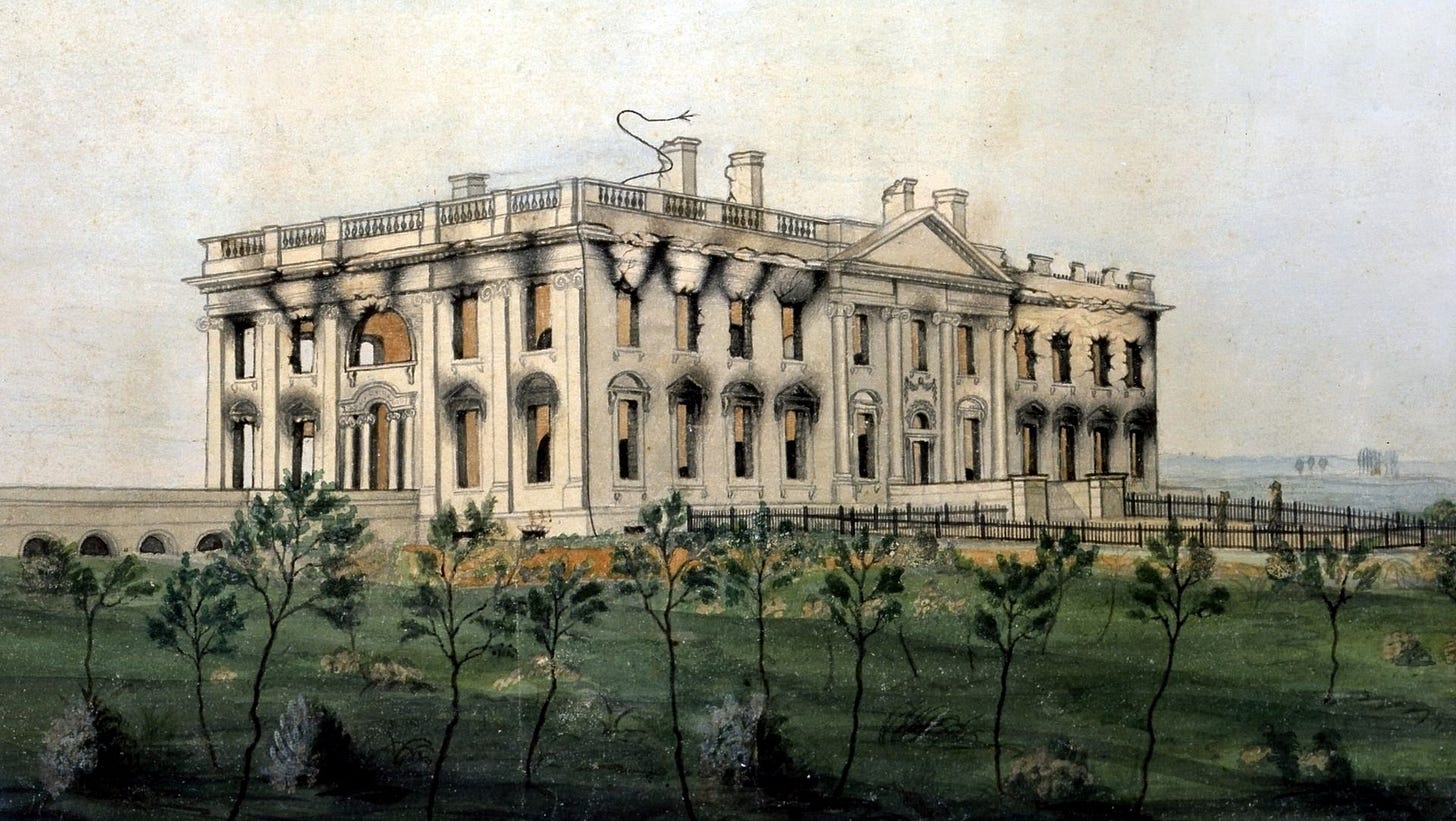

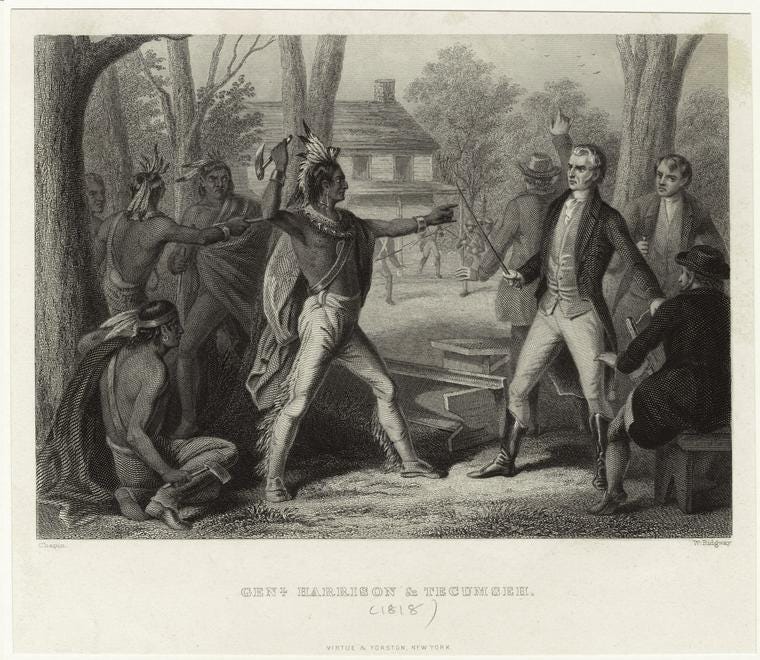

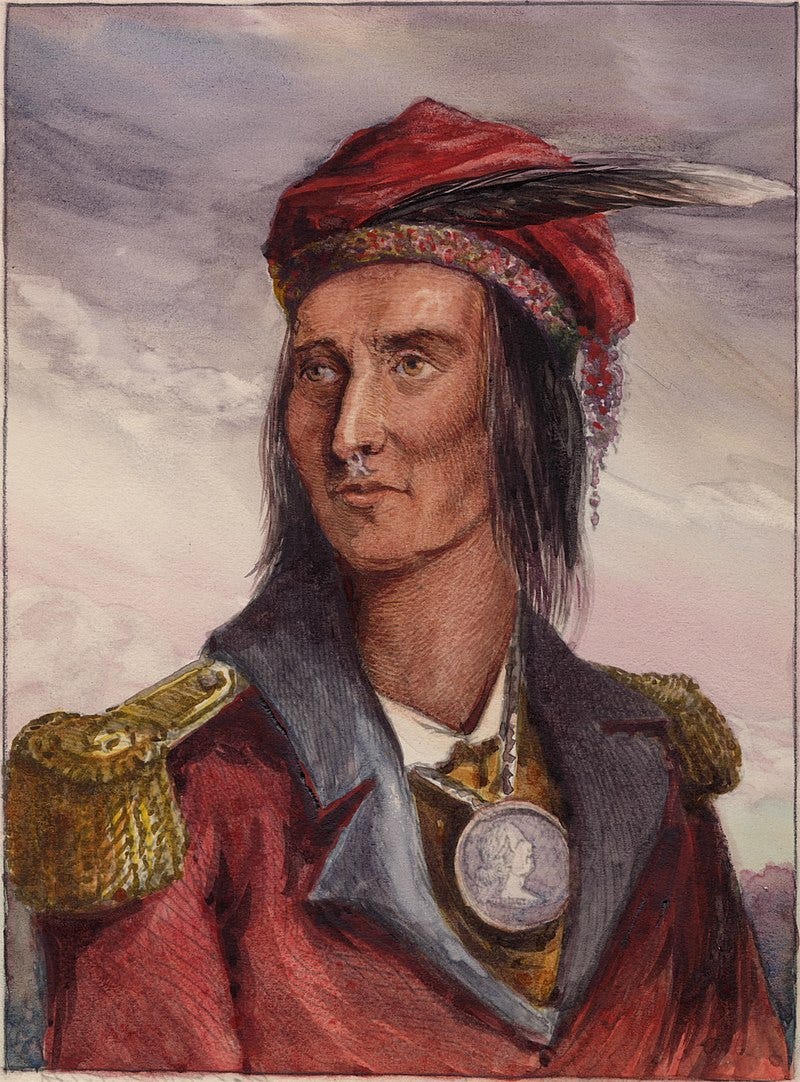

Britain maintained decent relations with the Indigenous People of the frontier, to the continuing anger of the Americans. As the US violently expanded into the Northwest Territory, Indigenous nations formed a confederacy centered around Tecumseh, a Shawnee warrior. The British, seeking to play off them off their continental rival, armed many groups including Tecumseh’s Confederacy.

Tecumseh’s Confederacy had been at war with the US since 1810. The tensions had been building for years earlier, seeing raids and further expansion by the US. The fighting peaked with the Battle of Tippecanoe, in which both sides mauled the other to an indecisive end, but the Confederacy warriors subsequently withdrew. The British were accused of suppling of the Confederacy warriors as well as coordinating their efforts.

It was these tensions, as well as several diplomatic schisms1 that pushed the two nations to war. The American war aims were not, however, simply retribution and an end to impressment. The seizure of Canada was a primary war aim of the American Government. Today it is debated by historians, what they intended to do with it afterwards. Either as an object to trade for another territory, or as a target for annexation, the objective was to seize Canada.2

On 1 June 1812, President James Madison, with the approval of Congress, declared war on Great Britain. It was not a popular war. Several states, including most of New England, elected not to join the conflict, and thus provided neither men nor money for the war. New England and Maritime Canada also continued to trade throughout the conflict.

Warfare in the Napoleonic period

The Napoleonic Wars, of which 1812 was one, were fought by enormous armies of cavalry, artillery and infantry. American and British forces alike were equipped, trained and organized in the same manner.

Both armies used the same principal weapon: the flintlock musket. These were smoothbore guns, loaded one shot at a time through the muzzle, and were horrendously inaccurate. Effective ranges of these weapons was generally not more than 200m, and accuracy at that range was abysmal. The firing mechanism, the flintlock, used a spring-loaded flint that would, upon pulling the trigger, strike a pan full of black powder causing sparks, that would ignite the charge in the barrel. The bullets were large and slow moving by today’s standards. Often, a soldier could see the bullets heading towards him.

“The bullet is a crazy thing, but the bayonet knows what it’s about,” said Alexander Suvorov, the legendary Russian Field Marshall (1729-1800). The purpose of musketry was to weaken and demoralize the enemy until a bayonet charge could chase them from the battlefield. Cold steel was seen as the decisive element in combat well into the 1860s3, when US Civil War Generals still advocated for the bayonet charge even in the face of widespread rifle usage.

Musket balls travelled very slowly by the standards of today, and the large, soft lead balls caused hideous wounds. Often, these would require amputation of the affected limb, or a slow painful death from secondary infection if hit in the torso. Surgery was primitive, anesthesia a privilege of a lucky few, bacteria unknown, and cleanliness standards unheard-of. A soldier of the period was more likely to die of diarrhea as he was from combat. Historians have estimated that in this period, two soldiers would die of disease for every man killed in action.

Both sides in this conflict wore bright coloured uniforms, red for the British and dark blue for the Americans. This was not, as is popularly believed, as impractical in combat as it seems. Battles in the period were smoky, and after a very short time armies would be standing in literal clouds of grey gun smoke that would obscure sightlines and confuse officers. In this context, brightly coloured uniforms were a necessary practical measure to ensure effective command and control. Soldiers of the period generally had no winter uniforms, as campaigning would be suspended normally during the colder months.

The American and British armies were experimenting with rifles during the Napoleonic Period, but only the Americans fielded significant numbers of them in North America4. These were largely in the hands of militia, as hunting guns with rifling were more common than military rifles. The Kentucky Militia became the most famous users of rifles in the conflict.

Smoothbore cannon were the primary artillery of the period. These would fire a solid cannon ball, or sometimes a primitive explosive shell. Cannon balls would often be bounced in front of lines of soldiers, ripping through the ranks, dismembering soldiers. At close range, they would load grape, or canister shot, which would fire many small projectiles at close range in the manner of an enormous shotgun.

In Europe, battles such as Borodino, and Eylau, were decided by enormous charges of cavalry, often wearing armour. The latter battle saw 10,000 French horsemen charge the Russian lines at once. Cavalry, however, were logistical burdens; warhorses need good feed, and heavy cavalry only had a decisive role in large set piece battles. The War of 1812 saw very little cavalry fighting, as only the Americans had any5, and they just two regiments.

1812: the American invasion goes awry

The US plan of attack was a three-pronged maneuver, with the three armies active independently of each other to attack Lower Canada towards Montreal and Upper Canada across the Niagara, and Detroit rivers. Governor General of Canada George Prévost ordered his troops, a small force of regulars6 accompanied by militia (fencibles), to a defensive posture.

The Army of General William Hull arrived at Detroit after marching cross-country through the wilderness of the Northwest Territory and invaded British Canada at Sandwich (Windsor Ontario). Hull, almost certainly suffering from PTSD7, suffered a mental collapse and withdrew his army to Detroit after the forces of British General Isaac Brock arrived on the scene with Tecumseh’s Confederacy forces. When Brock crossed the river in August and besieged Detroit, Hull surrendered the fort and his army without a fight.

Brock, the senior field commander of the British forces, was a dynamic and aggressive leader who, upon the declaration of war, quickly made alliances with Tecumseh and other Indigenous leaders. In the 1812 and 1813 campaign, these proved an essential augmentation to the British forces, were present in all major engagements, and struck fear in the American troops. Myth depicts Brock as an enlightened figure who respected and admired the Indigenous allies. Reality is less admirable: Brock was a pragmatist who wished to wield the Confederacy against the Americans. His writing indicates he did not know or understand even, that Indigenous Nations were distinct from one another.

A second US army under General Stephen Van Rensselaer attempted to invade Upper Canada at Queenstown, by crossing the Niagara River in October. The lack of coordination between American armies meant that General Brock was able to hurry back to Queenstown and meet this threat, negating the massive numerical superiority of the US forces.

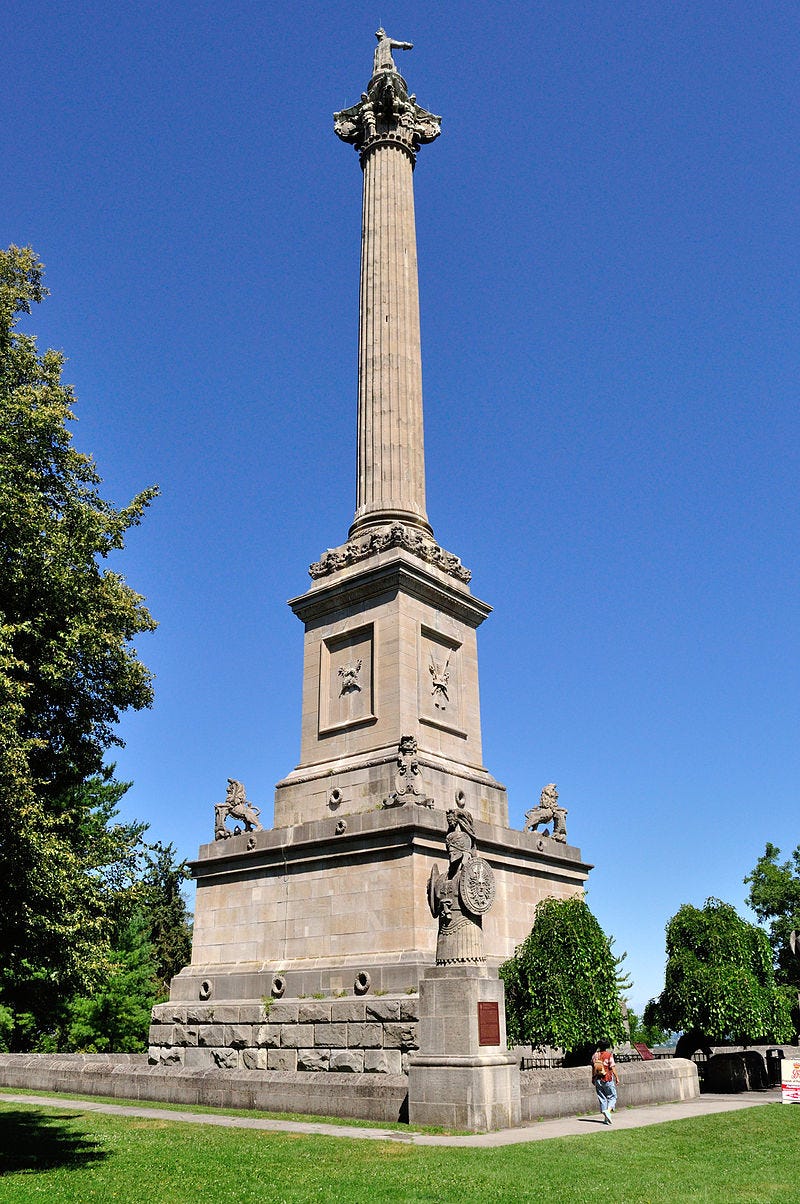

The Battle of Queenstown Heights, though small compared to other engagements in the war, was likely the most decisive in Canadian history. The Americans managed to cross with some of their forces but were soon pinned down by British artillery fire. Van Rensselaer was hit by several musket balls the second he hit the beach and was incapacitated.

In spite of the defensive fire, the US forces rallied, and a small detachment managed to take the batteries on Queenstown Heights. A series of desperate counter-attacks followed. Brock led a small detachment of the 49th Regiment of Foot in a counterattack up the heights and was struck down by a bullet to the heart. Legend has it that he cried “push on, brave York Volunteers,” but this is post-war propaganda. He was not leading that unit, and the wound, visible on his tunic in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, was almost certainly instantly fatal.

A subsequent counterattack led by Upper Canada’s Attorney General, Lieutenant Colonel John Macdonell failed, and Macdonell fell mortally wounded. A third counterattack was launched by Mohawk Warriors led by John Brant then attacked the beleaguered American positions.

The Mohawk counterattack was not itself decisive, but the moral effect was devastating. Hearing their war cries and seeing the disaster unfolding on the far bank, the US Militias refused to cross the river, stating their contracts did not require them to invade enemy country. Thus when the battle was in the balance, a significant percentage of the American forces refused to enter the fight.

Finally, after a full day of constant fighting, General Roger Sheaffe and additional British regulars arrived in the fight. Brant’s Mohawks joined them, and the American frontline collapsed in panic.

Having withdrawn to the river, and found no remaining boats, the Americans surrendered to the British forces, hoping to avert a massacre at the hands of the Mohawk allies. 955 Americans surrendered to the British forces, who at their highest point, numbered no more than 1,300 including the Mohawk warriors. Over 200 Americans were killed or wounded at a cost of 21 British dead and 85 wounded.

The third American Army attacked Lower Canada on November 20 and fought a small engagement at Lacolle, Quebec. In spite of having 5000 men to face 200 Mohawk warriors and 170 French-Canadian militia, the American forces halted, withdrew across the border, and refused to fight, with the militia again refusing to fight abroad.

The last actions of the 1812 campaign would see General, and later President, William Henry Harrison attempt to retake Fort Detroit, leading to the worst disaster for the US in the entire conflict. A detachment of his army under James Winchester, was attacked and destroyed in the Battles of Frenchtown. Though these occurred in January of 1813, this should be seen as part of the latter year’s campaign.

It was a massacre. The British/Confederation forces of General Henry Procter and Walk-In-Water of the Wyandot, smashed the American detachment, killing over 400, and capturing 547 out of a total strength of 1000 men.

What followed was called Rasin River Massacre. In the wake of the victory, the critically wounded Americans were left with the Confederation warriors by General Proctor, who likely knew what would befall them after the British forces left. The American wounded were killed or force marched, with at least 30, probably closer to 100 killed either in their sickbeds or on the side of the road when the couldn’t keep up.

The American fears of massacre at the hands of the Indigenous warriors were well justified, but this bears some examination. The Indigenous nations had been at war with the US since its inception, and as we well known, both British and American colonialism was absolutely devastating to the Indigenous people of Turtle Island. Thus the treatment of captured and wounded soldiers should be seen within the context of generations of genocidal war in which civilians on both sides were routinely murdered, and bounties were paid for the scalps of Indigenous people regardless of age and sex. The scalping by Americans of dead and still living Indigenous warriors and British soldiers was common in the conflict, especially after the Rasin River Massacre.

The 1812 campaign ended in massacre and failure. Far from conquering Canada, the Americans had actually lost territory to the British-Confederation forces. The invasions were mishandled, badly led, and occurred over broken terrain that sapped the strength of the US forces deployed.

Overseas, worse portents were on the horizon for the Americans. Napoleon, had just escaped Russia, having lost nearly 500,000 men in his nightmare withdrawal from Moscow. The combatants didn’t know it, but this would prove decisive in the years to come.

1813: The Americans rally

War in the 1800s (and even today) was very seasonal, and with the exception of Frenchtown, both sides settled into winter quarters. Both sides began a frantic shipbuilding programs on Lake Ontario and Lake Erie (the Welland Canal was not begun until 1824). For both sides, the goals and campaign directions remained unchanged, and at springtime, the war resumed in earnest.

On Lake Ontario, the naval balance was such that neither side was able to decisively confront the other. However, the US Navy was able to transport their forces to York, modern day Toronto. There, the Americans would be able to destroy the ships HMS Wolfe and HMS Isaac Brock, then under construction.

The 600 defenders, half of whom were militia, were unable to hold the Americans back and were pushed back, losing half their strength. As they withdrew, they fired the magazines in Fort York, causing a colossal explosion that, channeled by the shape of the building, acted as a massive directionally faced mine, killing and wounding dozens of American soldiers, including General Zebulon Pike, who was killed by flying debris.

York was subsequently looted and burned by the American forces. They were unable to advance to the capital of Upper Canada, Kingston, and eventually fell back. This battle cost the Americans far more than the losses they suffered; the burning of York turned the otherwise American-friendly population strongly against the invaders, something that would have immediate and painful consequences in the Niagara campaign.

The Americans again crossed the Niagara, this time with success, and seized Fort George. However, having taken a foothold, the Niagara Campaign would go little better for the US forces than it had the previous year.

At the Battle of Stoney Creek (June 6), an advanced force was discovered by a teen named Billy Green, who warned the British forces. The British attacked at night in a sudden violent bayonet charge, surprising the larger American force. Two Generals, Chandler and Winder, were captured along with 100 of their troops and the artillery. The British actually suffered proportionally much higher casualties, but the demoralized Americans withdrew.

Another thrust from Fort George was forewarned by a civilian named Laura Secord, who claimed to have heard the plan of attack, and warned the British forces. The battle of Beaver Dams (24 June) was a resounding victory in which 400 Indigenous Warriors and 50 British soldiers defeated a force of over 600 American regulars, capturing 462, who once again surrendered fearing massacre. In the words of their commander, Colonel Charles Boerstler, “For God’s sake keep the Indians from us!”

The Niagara Campaign was a failure for the US, but it was able to establish a foothold on the far side of the river. Success for the Americans would come from elsewhere.

On the Detroit River front, the British forces under Proctor continued offensive operations, besieging Fort Meigs and inflicting heavy losses on Harrison’s Americans, but were unable to take the position. From there, Harrison’s army pushed the British back until he was able to retake Detroit and cross the river.

The Battle of Lake Erie was the most important and decisive battle on the Great Lakes and saw the British Fleet under Robert Herod Barclay8 defeated by Oliver Hazard Perry. The improvised fleets, especially the British, were undermanned, and poorly officered. The battle left the British unable to control the lake, and their forces withdrew into Upper Canada.

The Battle of the Thames, near modern day Chatham Ontario, was a crushing defeat in which the larger American forces under Harrison defeated and routed Proctor’s Army, and in so doing, killed Tecumseh and destroyed his Confederacy. This battle was also unique as it featured one of the very few successful cavalry charges of the war.

The result of the Western theater’s collapse was devastating for the Indigenous Confederacy, which lost its leader as well as the primary theater from which they would be able to retake their homelands. For the British and Americans however, the Western theatre’s significance petered out, as the Niagara theater took precedence, and without success there, the campaigns farther west were irrelevant.

Late in 1813, the US Army once again tried to invade Lower Canada. On October 26 the Anglo-Indigenous forces under Canadian Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Salaberry defeated the American forces at Chateauguay. Another force was defeated at Crysler’s Farm, south of Montreal.

In the latter battle, in spite of being outnumbered 800 to 8,000, the British forces robustly defeated the American force which then retreated back across the border, losing over 400 of its number. Throughout the conflict, the Americans had expected to be greeted as liberators9 by the Francophone Catholics who they assumed would rise up against British oppression. Instead, their resistance showed the Americans that invading Lower Canada would be much harder than anticipated.

On December 30, 1813, the British Army under Major-General Phineas Riall, struck at Buffalo. The operation destroyed several ships that were under construction, and the town was burned. The operation was explicit revenge for the burning of Newark (Niagara-On-The-Lake, Ontario) by American troops earlier in the year.

The most decisive battle of 1813 occurred not in North America, but in Germany. At Leipzig, the combined allied army of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden, 365,00 men, fought for three bloody days against Napoleon’s 195,000, defeating him and crippling the Grande Armee. After this crushing blow, the Napoleonic Empire was on its last legs, and by May of the following year, he would be exiled to Elba. Though the two sides didn’t know it, operations in 1814 would see a massive change of relative strength.

The Americans were approaching their high-water-mark.

1814: Bloodletting

By 1814 both sides were exhausted. The British, having been at war for so long, were eager to end the conflict on the best possible terms. The USA, which had barely prepared for what would be a short war against a distracted power, found itself facing the most powerful empire in the world. Both sides wanted out of a conflict that had sucked in so much blood and treasure.

Napoleon’s imminent defeat added urgency to the American plans, as soon British reinforcements could be flowing into the colony. With the Western Upper Canadian campaign all but over, and the plans to “liberate” Lower Canada dashed, the Americans focused their efforts of the Niagara Campaign. In the third year of the war, and facing another occupation, the civilian population of Upper Canada had gone from apathetic to the Americans, to outright hostility since the burning of York and Newark.

The final invasion of Canada began at Fort Erie, when Winfield Scott led his men across the Niagara. Fort Erie was invested and surrendered after five days. Scott was a disciplinarian who had been captured and exchanged at Queenstown Heights. His brigade was well drilled and probably the best unit in the American Army.

The British commander, Major-General Finias Riall, awaiting reinforcements from York, dug in at the Chippawa Creek, in today’s Niagara Falls. Facing his force, was the American Army of the North, under Major General Jacob Brown, accompanied by a group of Chippawa warriors aligned with the Americans. Riall, unaware of the size of the force he was facing, ordered an attack on July 5.

The British advanced, and then upon finding themselves penned in on two sides by US troops, retreated, having suffered 500 casualties to the American 300. The fighting was intense, and a foretaste of what was to follow.

After proposed reinforcements failed to materialize, Major-General Brown decided to advance, and his army advanced to Queenstown, occupying it. All the while, British reinforcements were arriving. The Lieutenant Governor of Canada, Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond10, arrived with the troops to lead them in person.

On the morning of July 25, Winfield Scott advanced his brigade toward the church sitting on a small hill on Lundy’s Lane, where British forces were camped. This small church would become the focal point of the bloodiest battle of the War of 1812. Expecting a minor struggle, the battle gained a life of its own, pulling in reinforcements from both sides.

All day and into the night the battle see-sawed across Lundy’s Lane. The artillery battery at the church was captured, recaptured, and captured again. General Riall was wounded and captured by the Americans after his entourage wandered into their lines by mistake. Scott’s brigade was shredded.

Night fell, but the fighting continued, degenerating into a confused melee. Friend attacked friend in the dark, entire regiments were shattered by volleys of fire from their own side. Scott lay wounded after being hit by a spent cannonball. Brown was hit in the thigh and carried from the field. Riall, a prisoner, would lose an arm.

By midnight, the two sides were exhausted, and the fighting petered out. The US forces withdrew in good order, leaving the British, who were too exhausted to pursue them, in possession of Lundy’s Lane. It had been a bloody affair, with over 800 casualties on each side.

While the Niagara Campaign was reaching its bloodiest climax, farther afield, the war changed dramatically. A force of Royal Marines and Colonial Marines11, the precursors of a much larger force, raided Chesconessex Creek, opening the Chesapeake Bay Campaign.

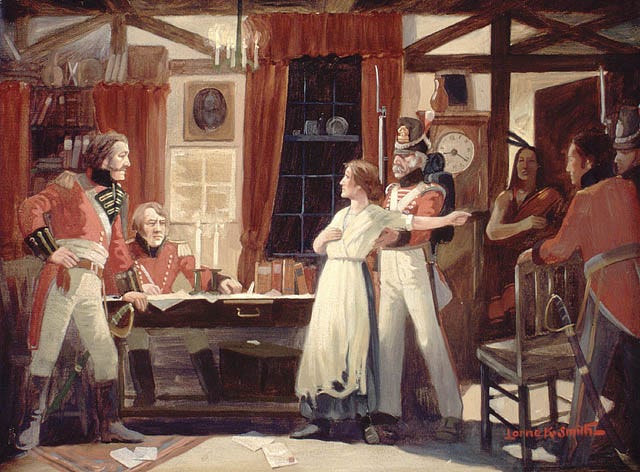

The raiding and naval bombardments of the Chesapeake were preparation for the invasion, which started at Alexandria, Virginia. On the 24th of August, the British and Americans clashed at Bladensburg. It was a dreadful performance. In spite of outnumbering the British 6900 to 1500, the Americans were decisively defeated. The British troops were not “Canadian,” nor were they inexperienced militia. These were the cream of the British Army; 85th Regiment of Foot and the British 44th Regiment of Foot were veteran formations of the Peninsular War, and the latter captured a French Eagle at the Battle of Salamanaca.

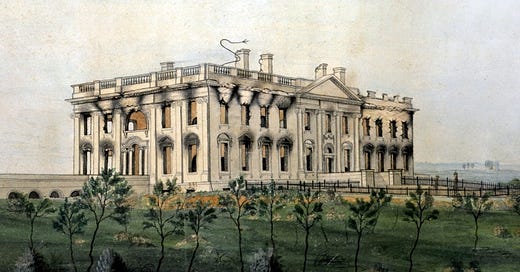

The rout that followed the battle became known as “The Bladensburg Races,” and was a humiliation for the US forces, who abandoned Washington D.C. President James Madison, and his administration fled before the British Army. Washington was looted by the invading troops, and the White House burned.

The fighting continued. At the battle of North Point, in Maryland, the British Army broke through the defenses leading to Baltimore but were unable to suppress the forts by naval bombardment and withdrew. In the process, the poem ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’ was written, and would eventually be adopted for the US National Anthem.

The Chesapeake Campaign objective was never to permanently occupy American positions there, but to destroy military and economic sites. With complete naval supremacy on the Atlantic, the British were able to pick and choose where to land and what targets to hit, and did so in order to pressure the Americans to seek terms. In this regard, the campaign was a success.

In Lower Canada too, the British Army had been reinforced. In September, George Prévost led a force of mixed Canadian militia and British Veterans, 11,000 in all, into New York. However, the Royal Navy was unable to secure Lake Champlain, the primary supply artery for the British invasion. The British Army was able to take Plattsburg, but the navy was defeated on the lake, and seeing that his supplies were in jeopardy, Prévost ordered a retreat back to Lower Canada.

Ghent and New Orleans

The bloodletting of 1814 had convinced all sides that it was time to negotiate an end to the war. Neither side’s offensives had been marked with lasting success, economic damage had been extreme, and casualties were spiraling out of control. The British Army by the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, actually had more forces in North America than it did in Europe, and more were flowing in.

According to historian and author Alexander Mikaberidze, by this time in the Napoleonic Wars, the British had suffered the same proportional casualties as they would suffer during the First World War. They were exhausted and war weary.

The United States had suffered grievous losses and economic hardship. The war had become an embarrassment, and even before the Chesapeake Campaign, the US economy had been badly damaged by the violent loss of trade with the British. It’s often forgotten today that after the American War of Independence, the British and American economies had actually become more profitable, and the loss of the Thirteen Colonies had greatly benefitted British maritime trade in the Americas. With war closing that buisness, both nations suffered badly.

Neither side had achieved a significant victory to claim real concessions from the other. The issue of impressment had become irrelevant with the end of the War of the Sixth Coalition in Europe.

On Christmas Eve, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed, theoretically usuring in what would be 200 years of relative peace between the two nations. In the treaty, both sides agreed to release all prisoners, and relinquish all occupied territories. As Pierre Burton put it, “It was as if no war had been fought, or to put it bluntly, as if the war was fought for no good reason.”

The dying, however, was not over.

December 14, unaware of the negotiations in Ghent, a British amphibious assault force appeared off New Orleans. These were the troops of Major-General Edward Packenham, veteran of the Peninsular War, and Brother-In-Law to the Duke of Wellington. His 8,000 men were mostly Peninsular War veterans but also included a battalion of the West India Regiment, composed of freed Black slaves and freemen.

On January 8, 1815, the last major battle of the War of 1812 took place, and for the British, it was a disaster from the outset. The British advanced against an entrenched enemy across swamps and wet ground and were cut to pieces by the American fire. Pakenham was killed, and 2000 of his 8000 men became casualties. The Americans suffered 71 casualties. The battle made the reputation of Andrew Jackson, who commanded the American Army at New Orleans, and became as President, the genocidal freak we know today, responsible for the Trail of Tears.

No battle in the War of 1812 optimizes the pointless butchery of this conflict more completely than New Orleans. In no way could it have ever effected the course of the war, and had electronic communication existed in 1815, it never would have occurred at all. Had the outcome been diametrically opposite; the result would have been equally irrelevant.

Winners and losers

When the guns of the War of 1812 fell silent, it was clear that neither nation had won the conflict. In Britain, the war barely registered next to the titanic struggle on the continent, and when it ended, collective memory of the conflict disappeared quickly.

The result for the US was humiliation. They had embarked on a short war that would, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, “would be a mere matter of marching,” and instead had lost their new capital. In the centuries that have followed, the US has selectively remembered aspects of the conflict, like New Orleans and Baltimore, without remembering the broader context of the conflict, or who started it.

Canadians have remembered an outsized, and fanciful depiction of the conflict thanks to the pro-Empire propaganda of the post-Confederation period. Canadians today like to remember the conflict as an underdog fight in which plucky little Canada defeated the big bad United States. Reality, as we have seen, in no way matches this depiction. In fact, it was quite the opposite.

“The notion of Canadians uniting their efforts and forging their nation in a struggle against their southern neighbors is a myth,” says Alexander Mikaberidze, in the book ‘The Napoleonic Wars.’ “For the vast majority of Canadians, the response to war was one of apathy, resistance to requisitioning, and desertion. It was only in the post-war years that the Canadian elites developed a propaganda narrative about “unshaken loyalty, fidelity and attachment shown by the Canadian volunteers and militiamen.””

However, this should not downplay the significance of the War of 1812 to Canada. The simple fact is that a key points, most prominently the Battles of Queenstown Heights and Montreal, Canada as it was, was very close to defeat and occupation by the United States. Canada of this period, other than Quebec, had little separate identity, and as such there is no reason to suspect any post-war Canadian independence would have been achieved, or even desired.

The Indigenous Nations of North America were the ones who truly lost this conflict. Tecumseh’s Confederacy disintegrated in the wake of his death and no Indigenous representation or agreement was included in the Treaty of Ghent. The Northwest Territory was consolidated and eventually fully annexed into the United States. In the South and West, the War of 1812 unleashed a period of intensive persecution of Indigenous People in today’s USA, seeing mass deportations, genocide, and uprooting of entire communities. Tecumseh surviving the Battle of the Thames is the big ‘what if’ of the conflict. Had he and his confederacy survived intact, they could have demanded terms from both governments, and perhaps the future of North America would have been very different.

Like the USA, Canada expanded West into more Indigenous territory after the treaty of Ghent. At first this was reluctant: the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) claimed much of what is now western Canada and it didn’t want to annex or settle it. However, with the USA expanding West, British interests meant they too, must expand westward, and the race to settle the Pacific began in earnest.

One of the most bizarre aspects of the war was the annexation of Old Oregon. The area of what is now Oregon, Washington and Idaho were held by the HBC, and as such were considered British territory. A British ship seized a small enclave there, which itself had been established illegally on British territory. Thus, when the Treaty of Ghent gave back all occupied territory, this included the areas that the Americans had claimed from the HBC.

The settlement of the West soon had Americans flooding into the region, and the Crown relinquished sovereignty, unwilling to see another conflict with the USA. Bizarrely, had the British not seized these sites in the War, they would not have been given back, and would today be part of Canada.

A forgotten story of the War of 1812 is the story of the Black Refugees. These were slaves freed during the conduct of the latter part of the war when British raids were seizing American plantations. They were settled in Nova Scotia, forming the core of what would become the Black Nova Scotian community, and were among the founders of Africville, the majority Black community in Halifax.

After the war

The post-war period saw an acknowledgment from both sides that conflict with one another was against their mutual interests. The Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1818 formalized the demilitarization of the Great Lakes, Lake Champlain and de-facto, the US-Canadian border. Small territorial conflicts over disputed territories would continue through the 1800s and some still exist today. Parts of Maine remain disputed, and after the US acquisition of Russian Alaska, so do parts of the Arctic.

As part of the reparations for the conflict, Britain agreed to give back all freed slaves, but eventually chose instead to remediate the costs involved. The British abolitionist movement was already well under way, and the idea of sending people back to enslavement was deemed unacceptable. The USA would retain slavery until 1862.

Some people managed to make their reputations in the conflict.

“Old Tippecanoe,” William Henry Harrison, was elected President in 1841, but died that April of Pneumonia that he had contracted at his inauguration. Given his record in fighting Tecumseh’s Confederacy, it is likely had he lived, he would have earned a reputation similar to that of Andrew Jackson.

Winfield Scott, brigade commander at Lundy’s and Chippawa, would become the Commanding General of the US Army. His career culminated with a different Manifest Destiny conflict; the Mexican War. He served briefly in a staff role during the first year of the US Civil War.

Oliver Hazard Perry, commander of the US Fleet on Lake Erie, has a class of US destroyers named after him.

British notables faired less well. After fighting the best of the French army, the backwater war in the colonies had little to celebrate. Prévost was called the Defender of Canada after the war, but his military reputation was not enhanced. In 1816, he demanded a courts marshal to clear his name after the Plattsburg operation, but died of natural causes before this convened.

One of the most interesting veterans of the war was Shadrack Byfield. A private in the 41st Regiment of Foot, Byfield participated in most of the battles of the Niagara Front and was badly wounded at the siege of Fort Erie. His arm was amputated after the battle, and he was invalided to civilian life, returning to Bradford on Avon, England. Byfield had been a weaver before enlisting, but his injury left him unable to work.

There were no medical supports for veterans or a social welfare state for the disabled. Byfield was one of the lucky ones; he developed a tool with which he could weave again using one hand. He married and probably died around 1850. His memoirs of the period are one of the few available that tells of common soldiers in the war.

Dispelling Myths

200 years later, the memories of the War of 1812 are clouded by propaganda and distance. As we have seen, many of the myths involved are largely over blown, or wildly inaccurate.

The American myths are centered around the success of the later battles, and a false notion that the war was defensive. The reality is that, whatever their intentions after the war, the goal of the USA was to conquer the Canadas. Popular myths of the successful defense of Baltimore and the Battle of New Orleans mask the fact that they had lost the initiative in an offensive war, and were forced to defend their core territoy. It was one of the earliest of the American expansionist wars that would see genocide of Indigenous nations, war with Mexico, and the settling of the West.

Canadian myths are more complex. The first and foremost of them being that the war was Canadian. This, as we’ve seen, is not accurate. Canada was the subject and objective of the conflict, and emphatically not a primary participant. Key men, like Drummond and Salaberry were indeed Canadian born, but we should not overstate their understanding of what a Canadian was. Nor was Canada an underdog, but rather a core part of the British Empire, the most powerful nation in the world after 1814.

Canadians see the War of 1812 as a conflict that “made” Canada. In one sense this is true; post-war propaganda placed the Canadian Empire loyalists at the center of the conflict and reconstruction, and this in turn created a communal identity surrounding the conflict. However, rather than seeing the conflict as having “made” Canada, instead, we should see it as having created the circumstances necessary to make Canada. Security concerns caused by American Manifest Destiny were absolutely important factors in the 1867 Confederation of Canada, and memories of the War of 1812, as well as the Fenian Raids (1866), and the Alaska Purchase (1867) were significant.

It can also be seen as Canada’s Original Sin. It represents the last time in which British-Canadian colonialism might have stopped, and allowed the Indigenous Nations of Turtle Island peace. Had they been represented at Ghent, had the Confederation survived the Thames, the future of North America could have been very different. It is not unreasonable to say that in the 1812 and 1813 campaigns, the British aligned Indigenous forces saved what is now Canada from occupation.

In return, when Canada Confederated, we became their oppressors.

Ian, February 12, 2025

Sources

Mikaberidze, Alexander; ‘The Napoleonic Wars’

Berton, Pierre, ‘The Invasion of Canada’

Berton, Pierre, ‘Flames Across The Border’

Brown, Stephen R, ‘The Company’

Graves, Donald E, ‘Field of Glory’

Bruce, Dickie, Kiley, Pavkovic, Schneid, ‘Fighting Techniques of the Napolonic Age 1792-1815’

There were many overlapping issues including the Orders in Council, and the French Continental System. These causes deserve more examination than can be covered in this summary.

To me it is not credible that they would have voluntarily surrendered occupied Canada, but this is opinion, not historical fact.

The last time I am aware of the British Army gave the order “fix bayonets” in combat was in the Iraq War 2003-2011.

The British had regiments of riflemen armed with the Baker Rifle, but to my knowledge, none were deployed to North America.

The only cavalry unit I am aware of on the British side was the 14th Light Dragoons, who fought on foot at New Orleans (1815).

Professional soldiers as opposed to militia.

A long serving US Army veteran, Hull fell into mental collapse when he heard the sound of the British Indigenous allies war cries.

As far as I know, not a direct relation of mine, but a member of the clan. Likewise for the Russian General who defeated Napoleon, Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly.

Heard that story before.

Along with Salaberry, he is one of a very few Canadian born leaders, though he never identified as such.

These were units of freed Black slaves that fought as Marines under the British flag, a subject worthy of far more discussion, but is outside the prevue of this piece.

The myths of 1812 in Canada are fairly pernicious. For at least 50 years post we had the “militia myth” - the belief that in the face of military need brave Canadians and Quebecois would but aside their differences, pick up their muskets and leave their normal lives to face the foe, and when complete, would put down their arms and resume their civilian tasks. The elites liked it because a militia of that type was cheap to maintain, and offered a comforting and unifying story to rally around. It completely ignored the Regulars and First Nations who were the most effective force in the war and ensured that Canada would always keep its military small because the militia was just that good. (The Militia Myth is a thesis in waiting)

The big one that keeps getting trotted out is that Canadians burned the White House as revenge for the Sack of York. Given that the British fleet that carried the troops who did it came from the Caribbean, I’m skeptical there were any Canadians there, let alone them doing it in revenge - burning public buildings happened quite often during fighting and I don’t think we need to attribute it to a deliberate act of revenge when, “it’s SOP” is right there.

Tecumseh might have been able to get a seat at the table for negotiations - he was the recognized leader of a territory the British would probably have been happy to recognize the sovereignty of (it was mostly in the US), but his death and the lack of a leader for the Confederacy who could demand and receive respect from both the British And the US meant the coalition fell apart and both colonial powers felt they could ignore the smaller polities as inconvenient to their designs on the region as opposed to a threat.

The War of 1812 - the British soon forgot it as a minor sideshow in the larger Napoleonic Wars, the Americans forgot what they wanted as they were in no serious existential danger. For Canada it was something because it was an existential conflict. And for the First Nations it was a catastrophe.

Excellent!