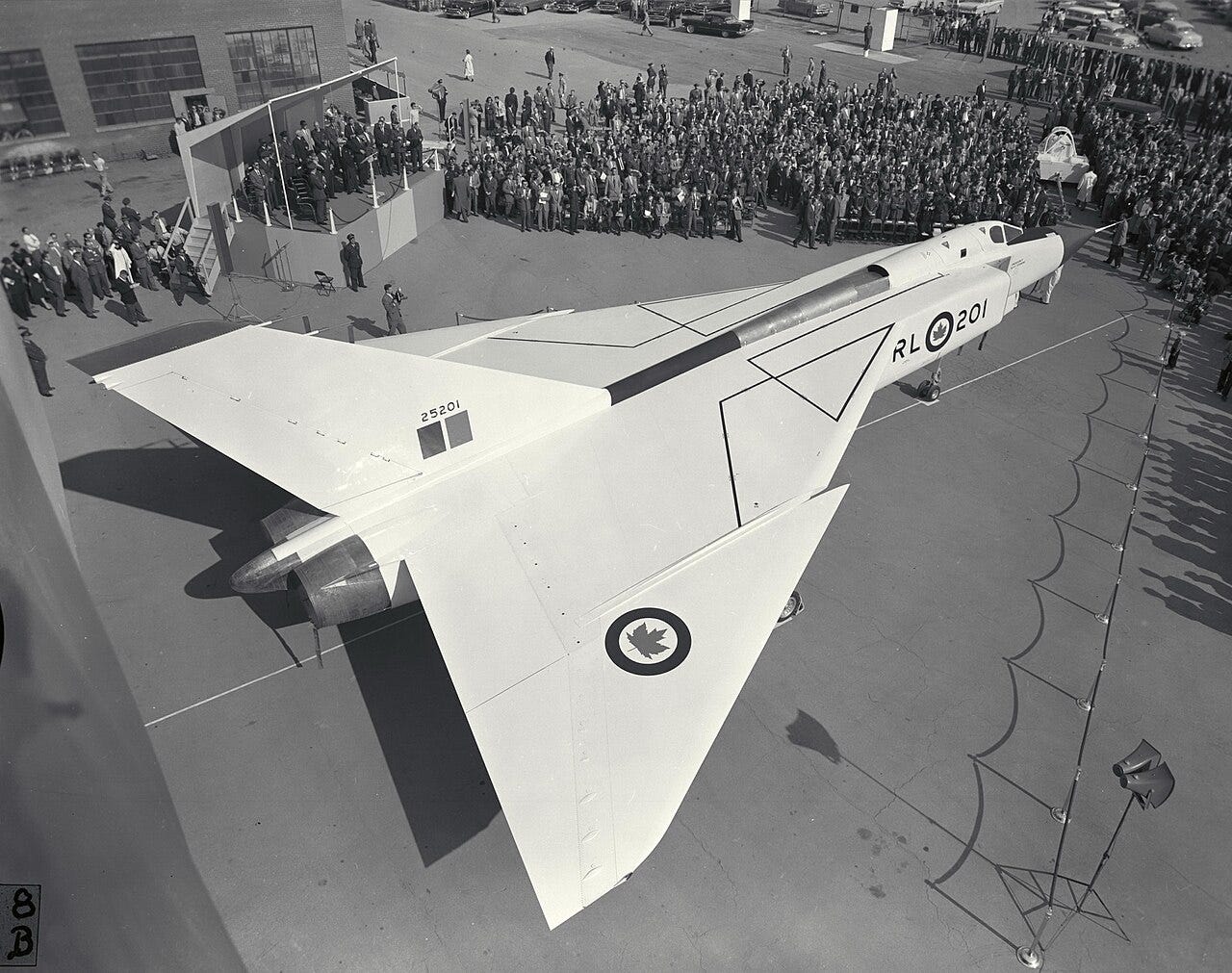

I recently watched the 1997 miniseries ‘The Arrow,’ a story about the design, building and the 1959 cancellation, of the Avro CF-105 Arrow interceptor. As a show, it has everything a made-for-CBC movie could have; heavy handed melodrama, anti-Americanism, anti-Conservatism, and Canada’s own Dan Ackroyd.

It’s a story of the finest piece of technology in 1959, about an exceptional Canadian company that made a miracle only to see it brought down by the Machiavellian intrigues of the Conservative Party and the United States. It is a film about Canadian Exceptionalism and the Canadian military industry.

Some of it is even true.

Unfortunately, reality is less exciting. The CF-105 was, as the Diefenbaker Government said at the time, obsolete. It was indeed, cutting edge, fast, likely would have broken speed records and been operational for decades. However, while the advent of the ballistic missile had not rendered manned fighter/interceptors obsolete, it did make the Arrow’s principal target; Soviet long-range nuclear bombers, obsolete.1

It was a threat that never existed. The hundreds or even thousands of bombers the CF-105 was designed to intercept were actually dozens. The Myasishchev M-4 (NATO codename: Bison), the aircraft that sparked the original RCAF requirement for the CF-105, was a failure and less than 150 were manufactured.

Today the Avro Arrow is almost unknown outside of Canada, but in Canada it is treated with a cultural reverence. Beyond the mystique, legends, myths and the objectively silly miniseries, the aircraft is a symbol of the Canadian Military-Industrial Complex (MIC), a vestige of the time when Canada made aircraft for war.

Birth: The World Wars

Canada has always had an arms industry, but the MIC is something beyond that. It’s fusion of military production and public policy. It’s one thing to manufacture arms, but it’s another to see your foreign and domestic policy dictated by the manufacture of those arms.

August 1901, saw the birth of the Canadian MIC. The Canadian Minister of Militia, Sir Fredrick Borden, was unhappy that Canada didn’t produce its own military rifles as the Royal Small Arms Factory that produced the Lee-Enfield service rifle was unwilling to set up license manufacturing in Canada. Canadian leaders at the time, acutely sensitive of issues surrounding Canadian identity, pushed to develop an independent, domestic and distinctly Canadian arms for the independent and distinctly Canadian military. This feeling was made more acute by the Boer War (1899-1902), during which the Canadian Army was bumped in priority for Lee-Enfield rifles by British orders.

The board that considered the merits of the two rifles was chaired by Colonel William Otter, the Canadian officer who had become famous for his role at the Battle of Cut Knife Hill.2 Competing against the Lee-Enfield rifle of British manufacture was the rifle of Sir Charles Ross that would bear his name.

In the history of the Canadian military there are few pieces of equipment that have been seen with such contempt, and fewer still that can claim to have killed so many Canadian soldiers as the Ross Rifle. The Ross was straight-pull bolt action rifle chambered in .303 British, the caliber used by the Lee-Enfield. As a target rifle it was outstanding. Indeed, after it was withdrawn from regular infantry service, Commonwealth snipers retained it for its exceptional accuracy. However, as an infantry rifle, it was a disaster.

The Ross had so little tolerance that even the slightly different brass casings of British manufactured .303 rounds as opposed to Canadian manufactured rounds was enough to jam the mechanism. The bolt thread would deform. Bayonets would fall off when firing. The rifle could be fired when put together incorrectly, causing the bolt to fly backwards and injure the user. Mud and dirt, the ever-present feature of the First World War, would jam the rifle terribly. There are accounts of entire platoons being left with half a dozen functioning rifles during the Canadian baptism of fire at the Battle of Ypres.

As Sergent Chris Scrivins of the 10th Battalion, The Canadian Division, later said; “I laid in a shell hole with four other men for a day and a half, and out of five Ross rifles in that hole, it took four of us to keep one of them working, banging the bolts out. As soon as you fired a round you had to sit down and take the entrenching tool handle to bash the bolt out.”

These rifles, unloved by all but a few, found their way into the hands of all sorts of militaries in the inter-war period. Spanish Republicans, White armies3, the Haganah4, and the British Home Guard to name just a few.

Thus it was that the Canadian MIC was born. Like so many staples of Canadian identity, it came into its own during the First World War (1914-18). As the Canadian military expanded, so too did the weapons industry. When the War began, the Canadian military was a militia force of semi-professional soldiers, when the war ended, an entire corps of four divisions plus supporting troops, navy and air forces. They all needed equipping.

Sam Hughes, Minister of Militia, had very specific plans for the Canadian Army. He wanted the force equipped by Canada, in Canadian uniforms, using their Canadian rifles. It was the first such initiative, but it would not be the last.

It wasn’t just defective rifles. The Canadian troops were issued paper soled shoes that melted before the soldiers even saw action. Ostensively bulletproof MacAdam shield-shovels, absurd devices that the user would poke their rifle though. Designed by Sam Hughes’ secretary, Ena MacAdam, they were entirely ineffective as shields, and having a big hole in the center also rendered them ineffective as shovels. The shovels, boots, and distinctively Canadian uniforms that were difficult to replace, were all supplanted by British items.

This should not be seen as disparaging to the Canadian manufacturing effort during the Great War as a whole; Canadian industry answered the challenge of the war with expedience, in general. From the misadventures of the Ross and the MacAdam shield-shovel, came the industrial powerhouse of Second 5World War Canada.

Canadian industry demilitarized by in large in time to see the need to remilitarize in 1939. In that role, Canada became a powerhouse. Enormous shipbuilding projects, aircraft manufacture and small arms factories. Canada manufactured everything from enormous Avro Lancaster bomber aircraft, Ram Tanks, warships, and soldier’s personal equipment.

Canada even armed the Republic of China in their fight against the Japanese. “Ronnie the Bren Gun Girl,” our equivalent of ‘Rosie the Riveter,’ was manufacturing machine guns destined not for the Canadian Army, but Chinese National Revolutionary Army, rechambered for Mauser ammunition.

Variances in manufacture notwithstanding, by the Second World War, Canada was manufacturing not Canadian designed equipment, but license manufactured copies of existing equipment. Thus Canadian manufacturing capacity can be seen as part of a doctrine what we today would call Coalition Warfare. Canadian industry sought independence, and indeed did gain local autonomy, but cost and allied pressure shifted production away from domestic innovation towards licensed production. The Canadian military and associated arms industry was thus designed with the understanding that the Canadians would be part of a much larger force, not as an independent entity.

Death: Cold War and the Avro Arrow

The Cold War saw Canada in one of the most powerful positions relative to our allies it has ever been in. Canada ended the Second World War with the 4th largest navy in the world (the Japanese, German and Italian navies being somewhat worse for wear), a large and experienced air force, and a substantial army.

The 1949 formation of NATO saw the position of Canada as a coalition member-state solidified. With the member states of NATO having clearly defined roles, equipment and supply would be built around those roles. Within an alliance such as NATO, each nation has a role, and for Canada, the defense of North America became paramount. The Canadian Navy was centered on anti-submarine work, the RCAF on air defense.

Maintaining a large military and associated MIC is easy during wartime; necessity trumps most other concerns, and while the War Pigs will still rake in their enormous profits, they won’t have much of a worry convincing people it’s the right thing to do. Peacetime and Cold War on the other hand, is more difficult. A mercurial threat from “the Reds” is no “international crusade against fascism,” and defense expenditures for a war that might not happen are much more difficult to justify.

Canadair, formally Canadian Vickers Ltd, was active aircraft manufacturer during this period. For the entire Cold War prior to the purchase of the CF-118, they manufactured most of Canada’s air force aircraft on license. The Saber (F-86), the CF-104 Starfighter (F-104) and the CF-5 Freedom Fighter (F-5) were all built by Canadair, the future Bombardier.

AV-Roe (Avro) Canada, the former manufacturer of such aircraft as the Lancaster and Anson, became a military aircraft designer in its own right. In 1950, the Avro CF-100 Canuck first flew. This was a two engine, two seat interceptor designed to defend the skies of North America from the Soviet bombers that, once again, did not exist. It was a solid, if unremarkable aircraft, and to date, the only Canadian designed fighter aircraft to enter production. It had Canadian designed Avro Orenda engines, and nearly 700 were built. Most were used by the RCAF, but a substantial number were also exported to Belgium.

Then came the Avro Arrow.

The Arrow was unlike any project the Canadian arms industry had ever participated in. The project, as well as the aircraft itself, was enormous. Not only the airframe, but the Orenda Iroquois engine, and the Velvet Glove weapons system were designed in Canada for use in the Arrow. When the CF-105 project was cancelled, Avro and its subsidiaries had over 50,000 employees, making it the third-largest corporation in Canada.

There are many books, stories, and documentaries about who exactly killed the Avro Arrow project, with titles like ‘Who Killed the Avro Arrow.’ The purpose here, is not to dissect the issue, but in broad strokes, capitalism and protectionism killed the Arrow. The US and UK had their own aviation industries at the time that would have suffered if a Canadian aircraft superseded them.

In a MIC, protectionism is more important than functionality and at no time was this more the case than in 1959. Canada caved, and in 1961 purchased the CF-101 Voodoo, an aircraft rejected by the RCAF when they issued the requirement for the Avro Arrow in the first place. Unlike the Saber and Starfighter, the CF-101s were built in the United States. Canada also bought several batteries of Bomarc surface to air missiles. These weapons were not very accurate, and as such designed to use nuclear warheads that Canada declined to purchase, making them useless even at intercepting the mythical bombers that weren’t coming in the first place.

None of this is to say that the Avro Arrow cancellation killed the Canadian arms industry; Canada was and remains a significant arms manufacturer. What cancelling the Arrow did, however, was alter the basis of ownership in the Canadian defense industry. Canada today produces pieces of military equipment, but they don’t greatly influence policy on a national level.

Until now.

Rebirth: Ukraine and Carney

“This starts with rebuilding, rearming, and reinvesting in the Canadian Armed Forces. The government’s generational investments in our Canadian Armed Forces will provide our military with the necessary tools and equipment to protect our sovereignty and bolster our security. This increase in investment also creates opportunities for the Canadian defence industry. We will reform defence procurement to make it easier and faster to buy Canadian-made equipment— supporting our domestic defence industry and creating high-paying careers.”

This is one of the opening paragraphs of the 2025 Canadian Budget, Chapter 4, ‘Protecting Canada’s Sovereignty and Security.’

The 2025 budget can easily be looked to as the rebirth of Canada’s Military-Industrial Complex. As already noted, Canada has been a producer of arms for much of its history. The Danish Military is equipped with Canadian C7 rifles, the Royal Saudi Land Forces were infamously provided with over 900 Light Armoured Vehicles (LAV) 6s built by General Dynamics Land Systems Canada. The Ukrainian Military uses a dizzying array of military equipment, a great deal of which was donated by Canada.

The Carney budget, however, brings this to a new level. In it, $6.6b is to be invested in the Defense Industrial Strategy, which is explain thus: “As the Strategy is implemented, starting with initial investments announced in Budget 2025, we will develop our defence industrial base so that more of our military capabilities are procured from Canadian supply chains.”

This includes an investment loan system for military equipment producers, investments into ‘dual use technology,’6 and natural resource exploitation under the guise of ‘defense.’ There will be a Defense Investment Agency “focused on providing the women and men in uniform with the equipment they need, when they need it.”

This, therefore, isn’t a massive funding increase just in the CAF/DND, but rather a massive funding gift to the Canadian weapons industry. Military investments are planned for every province and territory. A brick-and-mortar military budget. Indeed, a Military-Industrial budget.

How much of this investment will be directed at Canadian owned companies remains to be seen, but what is immediately clear is that it is production that is wished for.

It’s not without cause. The Russo-Ukrainian War has been an eye opener for the powers-that-be in NATO. Not only has NATO war stock been badly depleted, but it became clear within a year of the commencement of hostilities that rebuilding that war stock was a near impossibility while it was being expended as it was. Production now, has finally ramped up, but it is clear by this budget and the military budgets of many other nations in the NATO alliance that this was a major shock.

The shock has also been seen on the technology front. Drones dominate the battlefields of Eastern Ukraine. Cheap, easy to use, and lethal, the drone has supplanted many of the traditional roles of artillery, air support, mortars, and even tanks. Is this a trend or an aberration? We won’t know until the next war (gulp) but given their supremacy in this war and the Israeli genocide in Gaza, it seems likely that drones will continue to dominate the battlefield.

What this new CAF will look like in five years time remains to be seen, but if this minority Liberal government falls before that time it is unlikely that the Conservatives would change much vis-a-vis the military budget. Not only do brilliant minds think alike, but the Conservatives and Liberal minds do too.

The other question is this: what will we do with our new MIC?

If I had to guess (and ‘tis but a guess), I would say Canada is outfitting itself to become a new Arsenal of Democracy.7 It would seem that this government smells a tidy profit in war and wants their share. The production of arms is clearly being centered in government policy.

There is also the matter of personnel. War, as I have noted in other stories, is a personnel hog, and conscription is very much in vogue at the moment. The Canadian Government, with that in mind, proposed and then withdrew a program to enlist 300,000 civil servants in the supplementary reserve, after giving them one week’s military training. The breathtaking stupidity of this plan aside, it is clear that massive military mobilization is on the horizon as far as this government is concerned. This budget reflects that desire, the mobilization or not of 300,000 semi-willing professional bureaucrats notwithstanding.

I will conclude with the Oxford Dictionary definition of a Military Industrial Complex, and I will let you decide what we have on our hands:

“A country’s military establishment and those industries producing arms or other military materials, regarded as a powerful vested interest.”

Postscript

There is one other message to be found in the story of the Canadian Military-Industrial Complex. After the Avro Canada plant was shuttered forever, many of the experienced personnel went elsewhere, but the factories, still fully capable of production, did not.

Avro’s assets were taken over by Hawker-Siddeley Canada, and in their new role, these facilities produced train cars. Toronto’s GO Train, and the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) H-series subway cars are the surviving legacy of the Avro Arrow.

Maybe if we’re lucky, one day Carney’s weapons will become useful public transport too.

Ian, Nov 24th, 2025.

Select Sources

Dancocks, Daniel G, ‘Welcome To Flanders Fields,’ copyright 1988

Winchester, Jim, ‘Modern Military Aircraft,’ copyright 2010

The Arrow (TV Mini Series 1997)

Obsolescence in military equipment is a loaded concept. Long range, nuclear capable bombers were and still are present in many military inventories. Their role however is tertiary; these would be used in either a tactical strike on military targets, or as a follow up to mop up targets the ICBMs missed.

Daniel Dancocks, in ‘Welcome to Flanders Fields,’ described Col. Otter as almost becoming Canada’s General Custer, when at the his forces were surrounded and nearly annihilated by the Cree-Assiniboine warriors led by war chiefs Poundmaker and Fine Day. He and his force only survived because of Poundmaker and his warriors chose to let the Canadians flee.

“White” is the name given to the reactionary armies of the Russian Civil War, the name derived from the colours of the Bourbon monarchs in France. Very few “Whites" were actually monarchists in Russia but the name stuck.

The Jewish Paramilitary organization in Palestine that would become part of the Israeli Defense Force.

The Ram was not used as a tank during the war as it was already obsolete as compared to the Sherman, and as such the Ram was used largely a chassis for armoured personnel carriers and as unarmed artillery forward observer vehicles.

As the name suggests, dual use technology is equipment that is not inherently military but can be. Radio technologies, heavy vehicle manufacturing facilities, observation drones and ruggedized communication networks could all be classified as such. An example: during the Iran-Iraq War, Iraq as provided pesticide manufacturing and distribution equipment they purchased to use for chemical warfare.

A reference to the US role in the early stages of the Second World War in which, in spite of theoretical neutrality, they provided enormous supplies of matériel to the Allies.