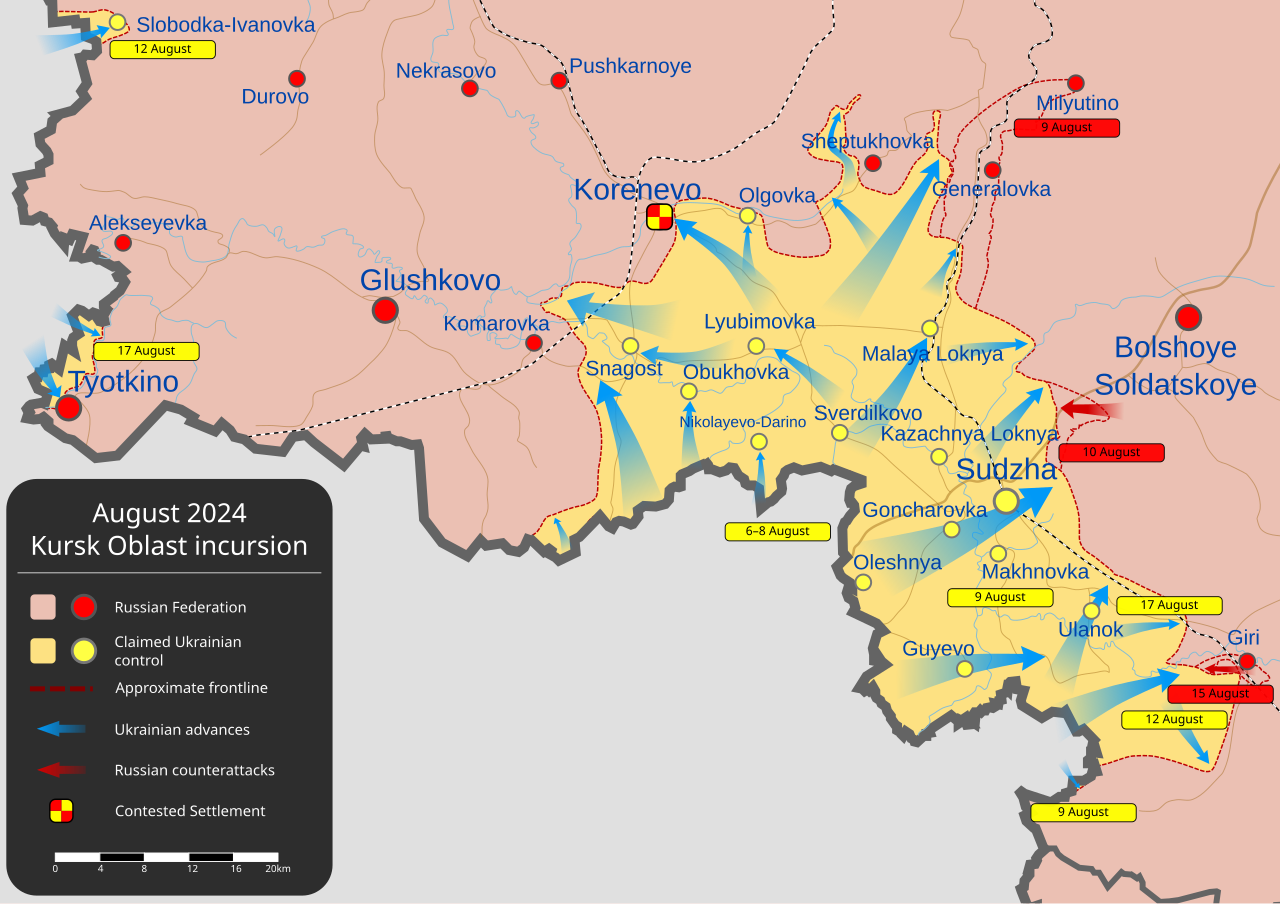

On August 6, 2024, the Ukrainian Army smashed through the thin Russian defense line in Kursk Oblast and, as of this writing, has pushed at least 20km into Russia on a 40km wide front1. Likely, more as of the time of this writing as this advance continues, though showing it is showing signs of slowing dramatically. Since this started, we’ve seen a great deal of speculation, so much so that I’ve been reluctant to write this article.

It’s hard to say what the outcome of this operation will be, though don’t ask the pundits of both sides. If you were to check Russian or NATO aligned news you would think you’re reading about two different events. Rather than speculate, or cheer for one side or the other like hockey teams, let’s look instead at the fundamentals of frontal warfare, and then at some historical parallels to this battle.

A key tenant of frontal warfare is the shaping and moving of reserves. It’s all well and good to be able to attack your enemy and win, but if they call in reserve elements and push you back, then what good was it? Even if you do hold an enemy trench line, what does that actually achieve?

The dilemma as early as World War I has been that the armies could destroy each other, but in order to advance they’d have to take over the ground they destroyed, whereas the defender could use railways and roads to shuttle reserves to crisis points, denying the long-awaited breakthrough.

By World War II, tanks and motor transport had become sufficiently effective and reliable that this became possible, but it shouldn’t mask the true nature of that war. In spite of the famous Blitzkrieg2, the majority of soldiers in the Second World War spent their time in muddy, interconnected trenches.

The Cold War innovations in weapons, far from making trench warfare less likely, have contributed to making it a reality. The Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), saw breakthroughs become extremely difficult to achieve in the face of anti-tank missiles, attack helicopters, and modern jet fighter-bombers. Iraqi and Iranian soldiers spent the majority of their days in dusty trenches.

There are of course, exceptions. The Gulf War (1991) featured large formations of mobile armour wheeling and fighting in the deserts of Kuwait and Southern Iraq, but the overwhelming imbalance of forces must be remembered. Total air superiority and the subsequent heavy damage inflicted upon the inferior and largely obsolete Iraqi Army meant that the war was over before it began, and this hardly demonstrates mobile warfare against a peer or near peer-opponent.

Now in 2024 we look to the Russo-Ukrainian War. During the opening months of the conflict the war was one of movement; the frontlines had yet to form and solidify, and ground changed hands quickly. However, once the Ukrainian Army stabilized their defensive lines, the war ground to a shuddering halt. With the notable exception of the 2022 Kharkiv Offensive, the lines have changed slowly since.

The situation of August 5, 2024, for Ukraine was one of crisis. The Russian Army is materially and numerically superior in most aspects to the Ukrainian Military and has used this advantage to grind down the Ukrainian Army. The battles of Bakhmut and Avdviikva, in Eastern Ukraine had the effect of wearing out and bleeding the Ukrainian Army by forcing them to defend a location they did not wish to abandon.

This is not unique to the Russian Army. The Ukrainian Kherson offensive was stopped with very little ground gained and heavy losses on both sides. As in the worst days of the First World War, the breakthrough proved elusive for both. The same technology seen in the Iran-Iraq War, plus the decisive addition of drone warfare, has made the offensive a costly undertaking.

As of today, August 20, 2024, the Russian Army has advanced some 30km beyond Avdviikva. It is a testament to the degree to which this war had stagnated, that this represents a clear, though costly, operational success. This was the situation that Ukraine faced when it launched the Kursk Offensive.

With all this in mind, why would you attack when you’re not only on the defensive, but losing that defensive?

The war is going badly for Ukraine. Heavy losses have forced truly draconian recruitment policies I have outlined elsewhere. The European Union donations are shrinking, and American support has proven shaky. Ukraine lacks the ability to produce close to the equipment the Russians have, and no economic power to purchase them.

Every day Russia become stronger; Ukraine weaker. Without changing the dynamic, they will lose.

There is nothing unprecedented in this.

In 1918, the German Army was presented a unique opportunity. The fall of the Russian Empire freed up so many troops from that front that, for the first time in years, the Germans had a decisive numerical edge on the Western Front. The high command knew it wouldn’t last; the Americans were coming into the war and would soon overwhelm the Germans with fresh troops. Facing inevitable defeat, they threw the dice. The Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle), was a colossal offensive designed to break the British Army, and smash open the Western Front before the war became unwinnable.

Unbeknownst to the Germans, it probably already was. The offensive crushed the British 3rd Army, and badly damaged adjacent units. The battle slowed, counterattacks and casualties diluted the German ability to advance, and the offensive staggered to a halt far short of the objectives. Eight months later, the war was over.

In 1944, Nazi Germany faced a crisis. On the Eastern Front, the Soviet Armies had just crushed Army Group Center during Operation Bagration. The successful breakout from the Normandy beachheads had cost Germany France and Belgium. Allied bombers were smashing the German oil industry. Knowing that they would be crushed eventually, Hitler, against the advice of several commanders, decided on an attack in the West, Operation Watch on the Rhine, or Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein,

In what became known as the Battle of the Bulge to Americans, German Army Group B smashed through the thinly held US lines in Belgium. The intent was to destroy the American Army and seize Antwerp, cutting off many allied units. It was hoped by the proponents of this offensive3, that they would ultimately destroy the Anglo-American ability to fight on the continent, freeing up Germany to fight the Soviet Union on a more secure footing.

Like the Kaiserschlacht, it was likely that it could never have succeeded, but in both cases, these are judgements of hindsight. In both examples, the military in question, facing a deteriorating situation took the decision to use local or temporary superiority to smash a thinly held front and reestablish a war of movement. That these examples failed does not mean the decision is illogical; this again is the gift of hindsight.

These are also only two examples. Every modern frontal war has featured defensive attacks, they are a staple of modern warfare. They necessarily feature a defending power concentrating their top-tier units into a counterattack, sometimes into enemy territory, against a locally far weaker opponent. In both examples, the country involved was conscious that it could no longer win a war of attrition and was instead aiming for a knockout blow. Hindsight has shown the two primary examples failed, but that’s hindsight, and not very useful in the context of analyzing this offensive.

This comes to the inevitable question: will it succeed? I have a reasonable ability to make predictions, but I also once said the idea of this war even happening was asinine, so I will leave judgments to history. It’s also important to define what success is.

Since the opening of the offensive, Russia has moved no less than two regiments, five brigades, and two independent battalion4s into the area around the Kurst salient. For some context, that represents more frontline troops and combat power than the entire Canadian Armed Forces. However, many of these units have come from outside the Ukrainian Front, so it remains to be seen if that represents a sufficient dilution of Russian power in Donetsk.

Has the Russian offensive in Donetsk slowed down significantly? In short, no. That doesn’t mean it hasn’t worked, strategic effects like this would take weeks to be seen without factoring in the fog of war. The Russian Army is clearly attempting to maintain pressure in Donetsk, and so far, has succeeded in doing so.

What we have seen, is some of the stupidest, most delusional propaganda since the ‘Ghost of Kyiv,’ emanating from both sides of the conflict.

If you were to ask Ukrainian sources, the attack is basically a second Battle of Stalingrad (except the Nazis on the wrong side this time), a crushing victory that proves Ukraine will win the war.

If you ask Russian sources, this is the most egregious and underhanded assault on Russia imaginable, and the Ukrainians are trying to cause a nuclear disaster (Kursk has a nuclear power plant). They also make an argument that invading Russian soil is an act of aggression. I’ve said many times that the cause of this war is nuanced, and that both sides hold shares of the blame, but you can hardly complain that the country you are occupying you has invaded you back.

Both takes are clear signs propaganda poisoning.

There are two other considerations, however, that make this offensive at least appear more than just a battle or relief attack.

Ukraine and Russia still do buisness. In Sudzha, the town that the offensive has been centered on, there is the main pumping station for the GazProm liquid natural gas (LNG) pipeline that supplies Europe with Russian LNG. As we have seen with the NordStream sabotage, Ukraine is not above destroying pipelines, but if they destroyed this one inside Ukraine, they wouldn’t be able to fix it themselves, and they wouldn’t be able to turn it back on. This pipeline represents such a massive economic interest, that Ukraine by this offensive, finds itself holding a large portion of the European economy in the palm of it’s hand. $2 billion dollars worth of leverage with the countries that are currently proposing cutting or slowing aid to Ukraine.

Assuming the pumping station survives. Large armies blasting away at each other with high explosives next to a station full of LNG is a recipe for disaster as much as one for leverage.

The second factor is the fact that somehow, some way, this war will end. It will almost definitely end at the negotiating table. If Ukraine can hold onto these chunks of Russia, something that is by no means assured, they could swap them for territory in Ukraine. The Russian Government is aware of this of course and has stated publicly they won’t be negotiating on their territorial demands; Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, Luhansk, and recognition of their annexation of Crimea. Once again, time will tell.

I have no conclusion or take away here, besides cautioning you from taking too much from this battle. It is a battle; it appears to have gone well for Ukraine today and may go well for Russia tomorrow. It may have hastened the end of the war, or lengthened it. The history books of the future, if such a thing is allowed to exist, can rule on the outcome.

The one knowable fact here is that a lot of people who had hopes and dreams are being turned into corpses to feed the guns, and the guns will have their say.

Ian, August 20, 2024

The numbers featured in this article will be prone to erratic changes as the situation becomes more clear. Treat all, but especially anything from either combatant nation, with skepticism. They are often still useful for context and rough estimations.

‘Lightning War',’ was the German Army’s offensive doctrine during the Second World War, and was one of the precursors to modern mobile warfare and combined arms doctrines. This doctrine was not unique to Germany; Italy, the USSR, and the USA were all working on similar doctrines before the war.

There were many opponents of Wacht am Rhein in the German General Staff, but many of these felt the offensive should occur elsewhere, or with modified objectives, not that there should not be an offensive.

This source is the mapping website DeepStateMap, which is run by the Ukrainian Government. Between this, and the fact these numbers are likely changing daily, the exact statistics and units should be treated with caution.

I'm impressed with this drawing of historical parallels. So often the context in modern warfare reporting is lacking, because the long view of incidents and strategies is crucial in gaining a balanced perspective.